San Pablo

ARPA’25

São Paulo

LUCILA GRADÍN /

May. 28, 2025 — Jun. 01, 2025

Galería COTT will present a Solo Show by artist Lucila Gradín (Patagonia, Argentina, 1981) at the ArPa 2025 fair.

I

As humanity becomes aware of the severity of the environmental crisis and recognizes—fearfully—itself as a threat to the continuity of its own existence and that of other species on the planet, an ontological shift has occurred in the human and social sciences and even in scientific research. We humans have begun to observe with curiosity and respect life forms that, from an anthropocentric perspective, we had considered inferior or unintelligent. In this context, the existence of plants—always intertwined with other beings—is emerging from the decorative place to which it had been historically relegated, transforming into a critical space for political imagination about sustainable and multispecies futures.

As anthropologist Natasha Myers argues in a recent article¹, saying that plants and forests form the “lungs of the Earth” falls short. More powerful than any industrial plant, communities of “photosynthetic creatures” reorganize the elements on a planetary scale. As they exhale, they compose the atmosphere; as they decompose, they contribute matter to compost and feed the soil. Moreover, recent studies show that plants sing in ultrasonic frequencies while transpiring, moving massive volumes of water from deep underground to the highest clouds. And as if that weren’t enough, they absorb the gaseous carbon emissions produced so abundantly by the fossil-fuel-based economy. Unlike humans, plants know how to create habitable, breathable, and nourishing worlds for all other creatures; they quite literally breathe life into the Earth.

The relationship between women and plants has deep roots in human history. For centuries, women have played an essential role as farmers and keepers of herbal knowledge, using the properties of plants to nourish and heal their communities. However, with the rise of modern botany in the 18th century, a “monoculture of plant knowledge” was established, laying the ideological and scientific groundwork for colonial plantations and today’s industrial agricultural systems². In this process, not only has about 75% of global phytogenetic diversity and thousands of hectares of forest been lost, but countless Indigenous communities around the world have been violently dispossessed of their ancestral territories.

II

Over the past decade, artist Lucila Gradín (Bariloche, 1981) has collaborated with a team of homeopaths, healers, and philosophers to recover knowledge that honors plants as teachers and guides. A turning point in her work was the discovery that every medicinal plant is also a dye plant, leading her to understand the color they release as an expansive wave of healing. This idea is not new: in many cultures, the color plants produce when dyeing textiles is perceived as an extension of their healing properties, potentially transferable to the people who wear them³. However, Lucila is interested in exploring a much broader notion of well-being, one that includes reflection on how we can develop ethical practices with plant life—practices that take root and weave networks of care across the Earth. Since then, the artist has devoted herself to creating a herbarium of native, medicinal, and dye plants, whose colors she understands as translations of the relationships that define local ecosystems: the seasons, soil quality, surrounding biodiversity, access to water, sunlight, and more.

The methodology developed by Lucila challenges traditional narratives of Western painting—a discipline in which she was originally trained and where plant life has usually been a secondary or marginal object of representation. In contrast, the artist activates the dyeing metabolism of plants, allowing them to “paint.” The alchemy of color takes place in her studio—a space filled with pots, natural fibers, and of course, plants—that resembles a life-cooking kitchen more than a laboratory. Each species has a particular way of releasing its color; for some, the bark is used, for others, the leaf or root. Some must be used dry, others fresh. Yet the essential ritual is always the same: macerate, boil, and allow what the artist describes as a “body-to-body” encounter with the plant to happen—a presence that fills her lungs and every pore. Lucila then tests these living dyes on animal fiber and paper. Finally, on previously generated patterns, she intervenes with embroidery and weaving, daring to imagine a “more-than-human” dialogue that shifts her own artistic agency.

III

In Genealogía Vegetal (Vegetal Genealogy), her first exhibition at COTT Galería, Lucila explores traditional dyeing technologies used in two native American trees: Brazilwood (Paubrasilia echinata) and Logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum), whose histories reveal how European colonization turned regions of “high biodiversity” into extractive territories, drastically and violently reorganizing life on our continent.

Driven by high demand for the red dye extracted from its wood—which symbolized luxury in the European textile industry—the exploitation of Brazilwood marked the first wave of Portuguese occupation in the 16th century. The trade was so lucrative that early merchants began calling the region “Tierra de Brasil” (Land of Brazil), referencing the intense red color, which ultimately gave the country its name. Similarly, Logwood, also known as dyewood, was heavily exploited by the Spanish in the Yucatán Peninsula and other parts of Mesoamerica. Its wood was highly valued for producing purple tones, difficult to obtain with other plants.

The transformation of these trees into global commodities had devastating consequences: Indigenous communities were displaced and forced to work in semi-slavery conditions, while the natural environment suffered a severe loss of biodiversity. Although demand declined with the advent of synthetic dyes in the 19th century, the social and ecological scars remain, and both species are now protected due to their historical overexploitation. Vegetal Genealogy offers a poetic perspective on these little-studied episodes, which are nonetheless crucial to understanding how extractive capitalism was established in Latin America. The exhibition comprises three groups of works in which Lucila tests the dyeing capacities of these plants on various surfaces, allowing them to manifest through color and engage in a complicit dialogue.

The textile pieces Palo Brasil (2024) and Palo Campeche (2024) are presented stretched on frames, giving them a painterly impression. Both fabrics were submerged in plant dyes for several days, absorbing characteristic gradients of red and purple that create differentiated areas of color: darker and deeper at the top and bottom, and softer in the center. On these surfaces, Lucila embroiders and stitches with yarns of different colors. The embroideries interact with the color stains, tracing lines, crosses, and abstract forms that, in some cases, evoke natural elements like mountains, undulating landscapes, or drops of water.

Horizontes (2024) is a series of nine works on paper exposed to plant dyes inside a glass box for exactly twenty-four hours. The dyes rise uncontrollably, creeping and spreading across the paper, creating chance-based landscapes of soft pink gradients that intensify toward the top. At the center of each piece, Lucila embroiders a wavy strip in more vibrant tones, evoking a horizon and visually contrasting with the smooth surface. At the bottom, she weaves long strands of yarn that hang freely, giving a sense of fluidity and placing the works in a space between drawing and textile.

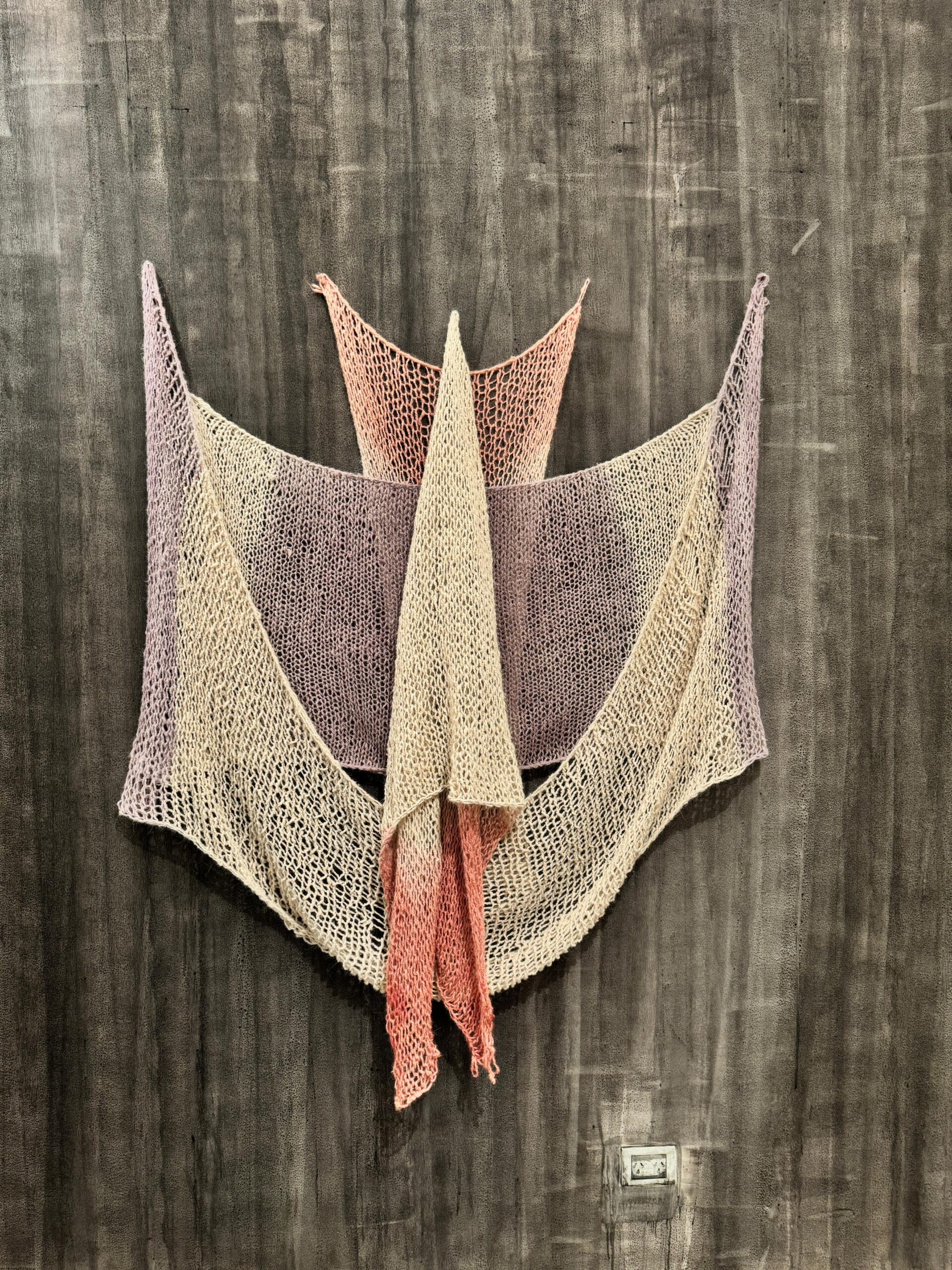

Fusión (2024) is a “fiber-sculpture” made with especially light and translucent llama wool. Unlike cotton or paper, wool absorbs dyes more subtly. The piece explores balance, using the material’s natural weight and fall. Combining red and purple hues, the wool is arranged in soft curves that fold over themselves before opening again. The organic and fluid form of the piece recalls female reproductive organs or even those of flowers, evoking the idea of fertility.

As a final gesture, Lucila has painted all the gallery walls with a dye extracted from yerba mate, infusing the “white cube” with the essence of this master and sacred plant of South America. Known for its properties that foster dialogue and connection, yerba mate creates a dense backdrop that evokes the lushness of a tropical forest, providing an atmosphere for the other works to integrate and share their stories with us.

IV

Life on Earth is not possible without the agency of plants. Considering them as subjects of rights and care raises ethical questions that may seem inconvenient from a “technocapitalist” perspective. However, as María Puig de la Bellacasa⁴ points out, we cannot allow these productivist paradigms to define how we value the “non-human” systems that support our existence. Plants are world-makers, and we must pay attention to them if we want to create livable futures. Yet, to recognize their essential qualities, we need to overcome “plant blindness”⁵, accept our profound interdependence, and broaden our definitions of life and intelligence.

By relating to plants as teachers instead of mere resources, Lucila’s work prefigures a way of making art that moves from scientific rationality to relationality. Indeed, by studying their qualities, acknowledging how their colonial histories intertwine with ours, granting them agency, and inviting them to collaborate, Lucila invites us to imagine a way of thinking that, for lack of better words, we could call “interspecies.” With this simple but powerful gesture, she reminds us that we are embedded in deep ecological assemblages since time immemorial. To think and feel these assemblages as communities we belong to is also to expand our political concern beyond the limits of human supremacy.

Florencia Portocarrero, curator

November 2024